| Physics and Astronomy |

|

Back to top

On this page

Contents Keeping track of dataThe structures we declared in the last last lecture have the disadvantage that we need to know in advance how many we will need and give them all names. But for many applications we want to be able to create and destroy them as the program progresses, for example if a user opens a new tab in a web browser. How do we create and keep track of these structures? Allocating structuresReminder: allocating a structureIn practice structures are nearly always dynamically allocated via pointers rather than declared as variables. We saw in a previous lecture that we can use malloc() to dynamically create simple structures. The mechanics work just as we would expect: struct thingy *p = NULL; p = xmalloc(sizeof *p); Having a function to create and initialise a structureIt's a very good idea to define a function whose job is to allocate the space for a structure and to do any initialisation as that way we have everything together in one place. The general form of such a function to allocate and initialise a new Thing with a double member called something is something like:

typedef struct thing {

double something;

// More members here...

} Thing;

// Allocate a new Thing and read the values from stdin

Thing * newThing() {

Thing *p = NULL;

p = xmalloc(sizeof *p);

printf("Please enter the value of something\n");

scanf("%lg", &p->something);

// etc.

return p;

}

Two points are worth mentioning here: 1. Do the initialisation in the simplest placeIn the above example we have just put a comment where we would initialise the rest of our new Thing. We have the choice of just putting the code directly in the function or of having a separate function to setup the Thing. If we choose to have a separate function then our newThing() function becomes extremely simple: // Allocate a new Thing and call setupThing() to initialise it.

Thing *newThing(void) {

Thing *p;

p = xmalloc(sizeof *p);

setupThing(p);

return p;

}

Our setupThing() function might look a bit like: // Read in the values of a Thing from the keyboard void setupThing(Thing *p) { printf("Please enter the value of something\n"); scanf("%lg", &p->something); // etc. } As always we just go for the simplest and clearest option in any given circumstance:

2. Choose how to initialise the structureAlthough for simplicity we often illustrate reading in the structure members from the keyboard, there are a number of other options. For example, it might be better to initialise all the members to zero which we can do using the following neat trick: // Set all the members of a Thing to zero

void zeroThing(Thing *t) {

Thing zero = {0};

*t = zero;

}

This works because:

We could then decide to call zeroThing() instead of setupThing(): // Allocate a new Thing and inialise it to zero (using sub-function)

Thing *newThing(void) {

Thing *p;

p = xmalloc(sizeof *p);

zeroThing(p);

return p;

}

or we may choose to do it all inside of newThing(): // Allocate a new Thing and inialise it to zero (all-in-one)

Thing *newThing(void) {

Thing zero = {0}, *p;

p = xmalloc(sizeof *p);

*p = zero;

return p;

}

The function callWhichever choice we make, the newThing() function is now essentially a drop-in replacement for malloc() except that it knows the number of bytes required and does any initialisation. A typical call looks like this: Thing *t = NULL; t = newThing(). It's a very good idea to define a function whose job is to allocate the space for a structure and to do any initialisation. RefactoringA common situation (and one we will encounter in the following mini-exercise) is when we have a chunk of code that is part of a larger function but we decide it would be better if it became its own separate function. This could be because:

This is an example of refactoring; the practice of tidyng our code in a way that doesn't change what it does but makes it easier to maintain and extend in the future. It's good practice to continually do this in small chunks rather than let our code turn into a mess and do a large "spring-clean". Notice how "Cut-and-Paste" (into a function) is better than Copy-and-Paste. A typical way to do this is to cut and paste the code into its own small function. For example, imagine we had decided not have a separate "newThing() function because we only needed to allocate a new Thing in one place. A little later we extend the program and need to alocate a new Thing in another place as well. The wrong way to do this would be to copy and paste the allocation code into another part of the program. The correct way would be to put the code inside a small function and to call that function twice. Often, although not in this case, the new function will require some arguments from the calling function. In our case the shell function is simply: // Allocate a new Thing and inialise it. Currently an empty stub // Choose the same variable name as the existing code to be moved. Thing *newThing(void) { Thing *p; // Move the allocation code to here return p; }

Example: a slightly more complicated allocation.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Human list | C program |

|---|---|

| Initialisation: | |

| Set the first person to "nobody". | Thing *firstThing = NULL; |

| For each new person or structure: | |

| 1. Find a new person. | 1. Thing *new = malloc(sizeof *new) |

| 2. Tell the new person their next person is the current first person. | 2. new->next = firstThing; |

| 3. The new person is now the new first person on the list. | 3. firstThing = new; |

Steps 1-3 are easy to add to our newparticle() function, we just need to:

- Pass the value of the first particle pointer as an argument

- Assign this to p->next (where p is the pointer to the newly allocated particle)

We have highlighted these two steps in the following newparticle function which allocates and initialises a new structure, and adds it on to the beginning of an existing linked list:

#include <stdlib.h> #include <stdio.h> #define NDIM 2 typedef struct particle { float x[NDIM]; float mass; struct particle *next; } Particle; // Allocate a new particle and add it to the start of the list struct particle * newparticle(Particle *first) { Particle *p; p = xmalloc(sizeof *p); p->next = first; // Now initialise exactly as before printf("Please enter the mass and x and y values.\n"); scanf("%f %f %f", &p->mass, &p->x[0], &p->x[1]); return p; } int main() { int i, n; Particle *first = NULL; printf("How many structures would you like?\n"); scanf("%d", &n); for (i = 0; i < n; ++i) first = newparticle(first); return 0; }

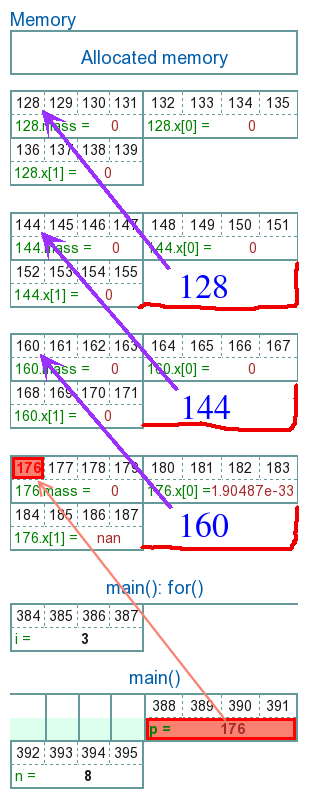

The call to newparticle()

At first sight the call to newparticle() looks very strange:

first = newparticle(first);The interpretation of this is "pass the current value of first to newparticle() and use the value it returns as the new value of first".

Notice also:

- We initialised the first element to NULL to show that the list started off empty: this is vital.

- We put all the checking that malloc() didn't fail into a utility function called xmalloc() that we can now use just like malloc() but without the tedious checking.

It is essential to initialise the first member of the list to NULL.

- Covert your newcuboid function to create a linked list

- To practice creating a list

- Inside main() make sure that the pointer to your cuboid structure is initialised to NULL. (This is now going to be the first member of the list of cuboids)

- Edit your newcuboid function so that it accepts a pointer to a cuboid structure, in the same way that newparticle() above accepts a pointer to a Particle.

- Change the statement inside your newcuboid function that sets the value of p->next to NULL so that it now sets p->next to the value of the pointer it received as a parameter.

- Change the call to your newcuboid function to pass it the value of the current cuboid structure (which should be NULL at this point).

- Build & run. Check the output is correct.. At this stage your next member should still be NULL as there is only one item in the list (ie there is no second item).

- At this stage main() should contain the following

three statements in successsion:

- A call to your newcuboid function.

- A diagnostic that prints out the values of your pointer and its next member.

- A statement that prints out the cuboid values such as mass etc.

- Build & run. Check the output is correct.. For the second diagnostic "%p" printout

the value of next should no longer be NULL

but should be the address of the first structure, something like:

p: 0xff8b3454 p->next: (nil) p: 0xff8b3514 p->next: 0xff8b3454

Notice how the second p->next is the value of the first p

Traversing a list of structures

Again, we can directly convert the process of traversing a linked list of humans into traversing a linked list of structures. We will use a temporary pointer p to refer to the structure under consideration at any one time.:

| Human list | C program |

|---|---|

| Initialisation: | |

| Make the first person on the list the "current person". | Thing *p = firstThing |

| Traversal: | |

| 1. If that person is "nobody" then quit | 1. if ( p == NULL) quit the loop |

| 2. Ask them the name of the next person on the list and make him or her the new current person.. | 2. p = p->next |

| 3. Go back to step 1 | 3. Go back to step 1 |

Using a for() loop

The loop above for traversing a linked list of structures fits well into a for() loop:

| Initialisation | Thing *p = firstThing |

| Test | p != NULL |

| Increment | p = p->next |

for (p = first; p != NULL; p = p->next)

printf("%f (%f, %f)\n", p->mass, p->x[0], p->x[1[);

A complete example for study later

#include <stdlib.h> #include <stdio.h> #define NDIM 2 typedef struct particle { float x[NDIM]; float mass; struct particle *next; } Particle; // Allocate a new particle and add it to the start of the list struct particle * newparticle(Particle *first) { Particle *p; p = xmalloc(sizeof *p); p->next = first; // Now initialise exactly as before printf("Please enter the mass and x and y values.\n"); scanf("%f %f %f", &p->mass, &p->x[0], &p->x[1]); return p; } int main() { int i, n; Particle *first = NULL; printf("How many structures would you like?\n"); scanf("%d", &n); for (i = 0; i < n; ++i) first = newparticle(first); for (Particle *p = first; p != NULL; p = p->next) printf("Mass: %f position: (%g, %g)\n", p->mass, p->x[0], p->x[1]); return 0; }

To go over every element of a linked list use:

for(p = first; p != NULL; p = p->next)

- Traverse your linked list of cuboids

- To practice traversing a list and to check the creation of the list.

- Comment out the diagnostic "%p" statement inside main().

- After you have setup the linked list of cuboids, create a for() loop like the one above to traverse the list printing out each cuboid. (You can just resuse the printf() statement you already have.)

- Build & run. Check the output is correct.. Your second loop should print out the same cuboids as the first one but in the reverse order.

- Now before the fixed loop that creates two cuboids, ask the user how many they want and modify the loop to create that many. (You will need to declare a variable to hold the number of cuboids required.)

- Build & run. Check the output is correct..

Preserving the order of the list

Our current newparticle() function creates the list in reverses order. This is not a problem if this is just a way of keeping track of the items, but it may be that the order is in fact significant. If we wish to preserve the order we can tweak the algorithm slightly:

- Allocate a new structure and set its next member to NULL

- If the list is empty just return the address of the new

structure.

Otherwise: - Find the last member of the current list.

- Set its next member to point to the new structure.

- Return the address of the first member of the list.

Note that in this case the start of the list changes only if the list was initially empty.

The code for finding the last element of the list is similar to the code for going over the whole list except that instead of stopping when The code looks like this:

// Allocate a new particle and add it to the END of the list struct particle *newparticle(Particle *first) { Particle *p, *last = first; p = xmalloc(sizeof *p); printf("Please enter the mass and x and y values.\n"); scanf("%f %f %f", &p->mass, &p->x[0], &p->x[1]); p->next = NULL; if ( first == NULL ) return p; // New list // Find the last element while(last->next != NULL) last = last->next; last->next = p; return first; }

Removing and freeing a member of a list

This introduces an extra complication: as well as freeing the structure itself we also have to remove it from the list.

To remove the first member of a list we simply set the new first member to old_first->next and free old_first. For every member except the first we find its predecessor and change its next pointer to the next of the one we want to free:

Initial list

- A -> B -> C -> D -> NULL

After removing 'B'

- A -> C -> D -> NULL

free(B)

After removing 'A'

- C -> D -> NULL

free(A)

If we are removing the first element of the list then the first element of the list will be the former second member (or NULL)

Otherwise we must traverse the list looking for the to-be-deleted member's predecessor

Two things to look out for

It would be good to check for two other possibilities:

- The case when the function is asked to remove "nobody"

(or NULL in pointer-speak). This may seem strange ("if there

is nothng to do why would they bother to call it?") but

remember two of our core principles for functions:

The purpose of a function is to make life easier for the person calling it.

And its consequence:

Decisions about what a function should do, or whether the function should exist at all, are usually answered by asking the question "what makes it easier for the person who calls this function?"

And it is easier to write:

freesomething(pointer);

Than:

if (pointer != NULL) freesomething(pointer);And it is also safer for our function to do the check than for it to crash.

- The possibility of a mistake, ie asking to remove something that is not actually a member of the list. We will discover this when we go down the list looking for the predecessor of our "to go" member: if we get to the end without finding our predecessor we have made a mistake.

- A variation of the above is that the list is actually empty.

It's perfectly OK to ask the function to remove "nothing" and the function must handle this.

Functions should try to check for common errors in calling them.

Removing a member of a list

Stripped-down version

Let's first look at a version that does not do any of the error checking:

/* * Stripped-down free particle without checking. * Free Particle "togo" and return the new first Particle * "first" must be the existing first member of the list */ struct particle * freeparticle(Particle *togo, Particle *first) { Particle *parent; if (togo == first) // Is it the first one? first = first->next; else { // Find togo's predecessor: for (parent = first; parent->next != togo; parent = parent->next) { // Empty loop } parent->next = togo->next; } free(togo); return first; }

The empty for() loop looks a little unusual, it is because the mere act of finding the end of the loop is actualy the task we want to acheive.

Full version

Here we incorporate the "nothing to do" and error checks:

/* * Free Particle "togo" and return the new first Particle * "first" must be the existing first member of the list */ struct particle * freeparticle(Particle *togo, Particle *first) { Particle *parent; if (togo == NULL) // Do nothing return first; else if ( first == NULL ) { fprintf(stderr, "Trying to remove something from an empty list!\n"); return NULL; } if (togo == first) // Is it the first one? first = first->next; else { // Find togo's predecessor: for (parent = first; parent->next != togo; parent = parent->next) { if (parent->next == NULL) { fprintf(stderr, "%p isn't in the list!\n", togo); return first; } } parent->next = togo->next; } free(togo); return first; }Step through a complete example of this code

Forgetting to free() the data

As always, forgetting to free() the data leads to "orphaned" blocks of allocated memory.

Step through a version of this code that forgets to free the memory.

Forgetting to free() the data leads to "orphaned" blocks of allocated memory.

Summary

The text of each key point is a link to the place in the web page.

Allocating structures

- In practice structures are nearly always dynamically allocated via pointers rather than declared as variables.

- It's a very good idea to define a function whose job is to allocate the space for a structure and to do any initialisation.

- Structure which themselves contain dynamically allocated members will need more than one call to malloc().

- When freeing data we must take care of any pointers pointing to it.

- One solution to the problem of remembering the addresses of an unknown number of chunks of allocated memory is for each allocated chunk to remember the address of the previous one.

- The structure definition contains an extra member which is a pointer (usually called "next") to the next structure in the list.

Creating a linked list of structures

Traversing a list of structures

Removing and freeing a member of a list

- If we are removing the first element of the list then the first element of the list will be the former second member (or NULL)

- Otherwise we must traverse the list looking for the to-be-deleted member's predecessor

- It's perfectly OK to ask the function to remove "nothing" and the function must handle this.

- Functions should try to check for common errors in calling them.

- Forgetting to free() the dataleads to "orphaned" blocks of allocated memory.